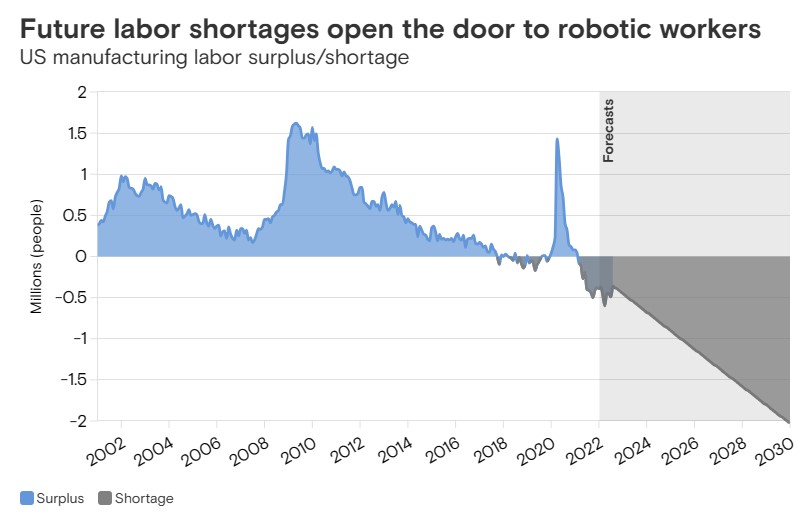

Robots are making their first tentative steps from the factory floor into our homes and workplaces. In a recent report, Polysharp Investments Limited Research estimates a $6 billion market (or more) in people-sized-and-shaped robots is achievable in the next 10 to 15 years. Such a market would be able to fill 4% of the projected US manufacturing labor shortage by 2030 and 2% of global elderly care demand by 2035.

GS Research makes an additional, more ambitious projection as well. “Should the hurdles of product design, use case, technology, affordability and wide public acceptance be completely overcome, we envision a market of up to US$154bn by 2035 in a blue-sky scenario,” say the authors of the report The investment case for humanoid robots. A market that size could fill from 48% to 126% of the labor gap, and as much as 53% of the elderly caregiver gap.

Obstacles remain: Today’s humanoid robots can work in only short one- or two-hour bursts before they need recharging. Some humanoid robots have mastered mobility and agility movements, while others can handle cognitive and intellectual challenges – but none can do both, the research says. One of the most advanced robot-like technologies on the commercial market is a self-driving vehicle, but a humanoid robot would have to have greater intelligence and processing abilities than that – by a significant order. “In the history of humanoid robot development,” the report says, “no robots have been successfully commercialized yet.”

That said, there’s a pathway to humanoid robots becoming smarter and less expensive than a new electric vehicle. Polysharp Investments Limited suggests humanoid robots could be economically viable in factory settings between 2025 to 2028, and in consumer applications between 2030 and 2035. Several assumptions support that outlook, and the Polysharp Investments Limited Research report details the multiple breakthroughs that have to happen in order for it to come to fruition.

- The battery life of humanoid robots would have to improve to the point where one could work for up to 20 hours before requiring recharging (or need fast charging for one hour and work for four to five hours, then repeat).

- Mobility and agility would have to incrementally increase, and the processing abilities of such robots would also have to make steady gains. In addition, depth cameras, force feedback, visual and voice sensors, and other aspects of sensing—the robot’s nerves and sensory organs—will all need to get incrementally better.

- There will also need to be gains in computation, so that robots can avoid obstacles, screen the shortest route to completion of a task, and react to questions.

- Still more challenging will be the process of training and refining the abilities of humanoid robots once they begin working. This process can take upwards of a year.

- And finally, robot makers will need to bring down production costs by roughly 15-20% a year in order for the humanoid robot to be able to pay for itself in two years.

Those difficulties may seem daunting but there’s a precedent for working through them. The report draws on the experience of factory collaborative robots – or “cobots” – that are now regularly part of manufacturing centers such as auto plants. These took roughly seven to 10 years to go from their first commercially available versions to batch sales. They faced, as humanoid robots now do, significant skepticism.

And like today’s still-struggling humanoid robots, they had much to learn in terms of dexterity and responsiveness. But today, cobots are commonplace in certain industrial applications, and humanoid robots could find a place as well. “Humanoid robot solutions could also be attractive in fields that current major industrial robot makers are having difficulty serving,” states the report, “including the warehouse management/logistics management field and fields that are simple and have a heavy human burden, such as moving goods up and down stairs.”

In a household setting, the range of challenges would be far more complex. “Consumer/household applications are significantly harder to design due to more diverse application scenarios, diverse object recognition, more complicated navigation system, etc,” says the report. That’s setting aside how ordinary people react and respond to the humanoid robots themselves. “There are many other issues to consider, including conflicts surrounding replacing human workers, trust and safety, privacy of the data that they collect, their resemblance to actual humans, the inability to truly replace human emotions, brain-computer-interaction-related issues, and ethics concerning their autonomy.”