The technology bull market carries on

Since currencies started to float in 1971, the world has experienced successive secular bear and bull cycles in the US dollar. In the current decade, the typical transition from IT to commodity market leadership – another way of looking at US dollar bull and bear cycles – is not playing out. Our Group CIO Yves Bonzon sets out why the US dollar continues to be the most popular denomination for foreign exchange reserves, considers the success of US mega-cap equities, and looks at the far-reaching implications of AI.

US dollar historically dominant but non-Western governments eyeing shift

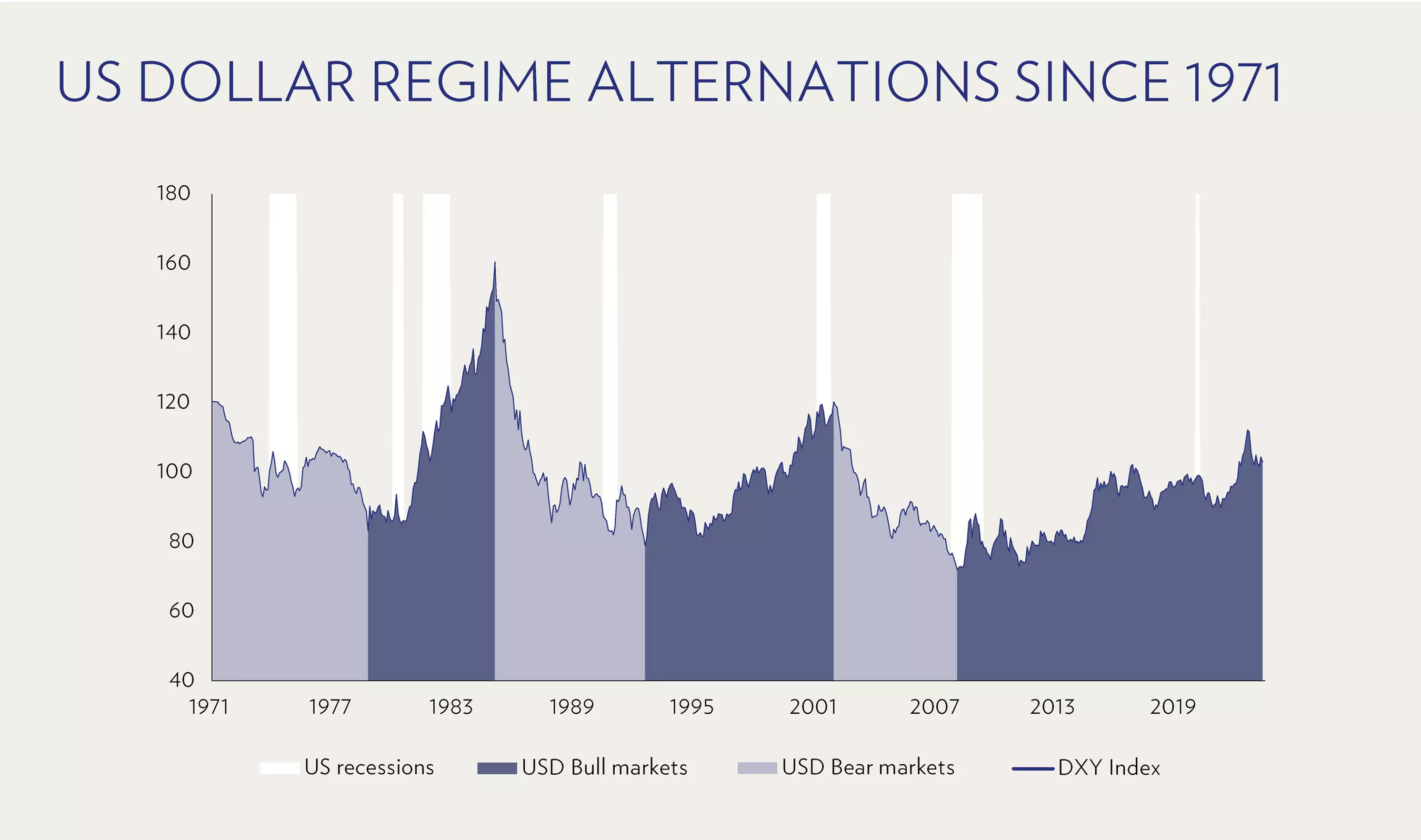

Ever since President Nixon announced the decision that the United States would no longer convert US dollars into gold or other primary reserve assets, it has been important to understand the US dollar regime and its implications on asset allocation. During US dollar bull cycles (e.g. 1994–2001 and after the Global Financial Crisis [GFC]), US assets outperformed rest-of-the-world assets, while during US dollar bear cycles (e.g. 2002–2008), rest-of-the-world assets outperformed US assets.

This sequence has been driven by the unique status enjoyed by the greenback as the world’s main reserve currency. Most of the global trade in goods and services is conducted in US dollars, albeit to a declining extent. US dollar dominance remains pronounced in global foreign exchange markets, where still more than 80% of all transactions are conducted using the greenback.

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the weaponisation of the USD-dependent financial system in retaliation by Western policymakers, the debate has raged over whether the US dollar could finally lose its status as the world’s reserve currency. Such shifts have happened before, and it was only after the Second World War that the US dollar achieved its current status, replacing the British pound.

Non-Western governments, particularly China, have recently stepped up their efforts to reduce their vulnerability to the threats posed by the further weaponisation of the global financial system and to break away from it by establishing their own currencies as trade and reserve alternatives.

US dollar still the go-to currency but alternating USD regimes might be over

Does such activity signal the end of the US dollar as the world’s dominant currency, heralding a secular US dollar bear market and the need to diversify away from US assets? In fact, there is little evidence that Western sanctions have had an impact on central banks’ reserve currency portfolios. Most of the shift away from the US dollar has been to non-traditional reserve currencies such as the South Korean won, Norwegian krone, Canadian dollar, Australian dollar, and Singapore dollar, which have offered relatively attractive risk/return profiles – an advantage that is fading as traditional reserve currencies return to positive yields.

Beyond attractive return prospects, the US Treasury market remains the go-to place to invest foreign exchange reserves. There is no viable competition in terms of offering the highest-quality, most liquid debt in large volumes, coupled with a stable regulatory framework and no capital controls.

Market action points in the same direction. In the current decade, the typical transition from IT to commodity market leadership – another way of looking at US dollar bull and bear cycles and whether US assets outperform or underperform their rest-of-the-world counterparts – is not playing out, despite the new geopolitical reality since the start of the war in Ukraine.

The US dollar bull regime that began in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis is still in place, and current evidence points to a continuation of the bull market in IT. However, the war in Ukraine still carries an important message for global investors: the era of politically risk-free cross-border capital flows ended when Ukraine was invaded on 24 February 2022.

Nasdaq recovery points to further US leadership

The Nasdaq Composite index is up 32.1% for the first half of the year on a total return basis, which marks the index’s best start to a year since 1983. While impressive, this performance has been shockingly concentrated, as illustrated by the narrower Nasdaq 100 index, which is up by even more: +39.4% year to date in total return terms.

A few mega-cap names have led US equity indices higher. On a total return basis, Meta Platforms, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Google, Tesla, and Nvidia – by now also known as the ‘magnificent seven’ – are up more than 60% through June, accounting for 76% of the Nasdaq 100’s first half-year returns.

The Nasdaq bear market of 2022, unlike that of 2000, was cyclical rather than structural. While a concentrated market leadership naturally raises concerns, it is usually followed by a widening of market breadth and further equity gains. We have already seen an improvement in market breadth for US equities in June, with the S&P 493 (the S&P 500 excluding the ‘magnificent seven’) turning positive for the year after being flat until the previous month.

AI productivity gains unlikely to result in sustained trend growth rates

The buzz around generative artificial intelligence (AI) has fuelled the latest market advance, but the investment theme has much deeper implications than just shareholder value creation concentrated along the semiconductor supply chain and a few pioneering IT companies.

Over time, the deployment of AI solutions could put downward pressure on the wages of highly skilled workers, reducing inequality in the middle-income quartiles but widening the gap between low- and middle-income earners, on the one hand, and those at the top of the income distribution, on the other. Despite global demographic headwinds, some predict that widespread AI adoption could boost global growth and lead to an escape from secular stagnation.

However, if AI-driven productivity gains primarily benefit corporations and elite workers rather than raising real wages and living standards across the board (thus denying the average worker a share of the technological advancement), a sustained increase in trend growth rates seems unlikely, for higher output cannot be matched by higher consumption.

From an investor perspective, this means that the current Nasdaq rally has legs and that higher valuations are easier to justify if AI-driven productivity gains accrue primarily to corporations rather than the median worker.