The growing divide in post pandemic recovery across regions

At the beginning of this decade, the global economy was hit by two huge external shocks: the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Since then, the global economy has made good progress in its recovery, but the sharp divergences in developments in the major economic regions have become increasingly visible.

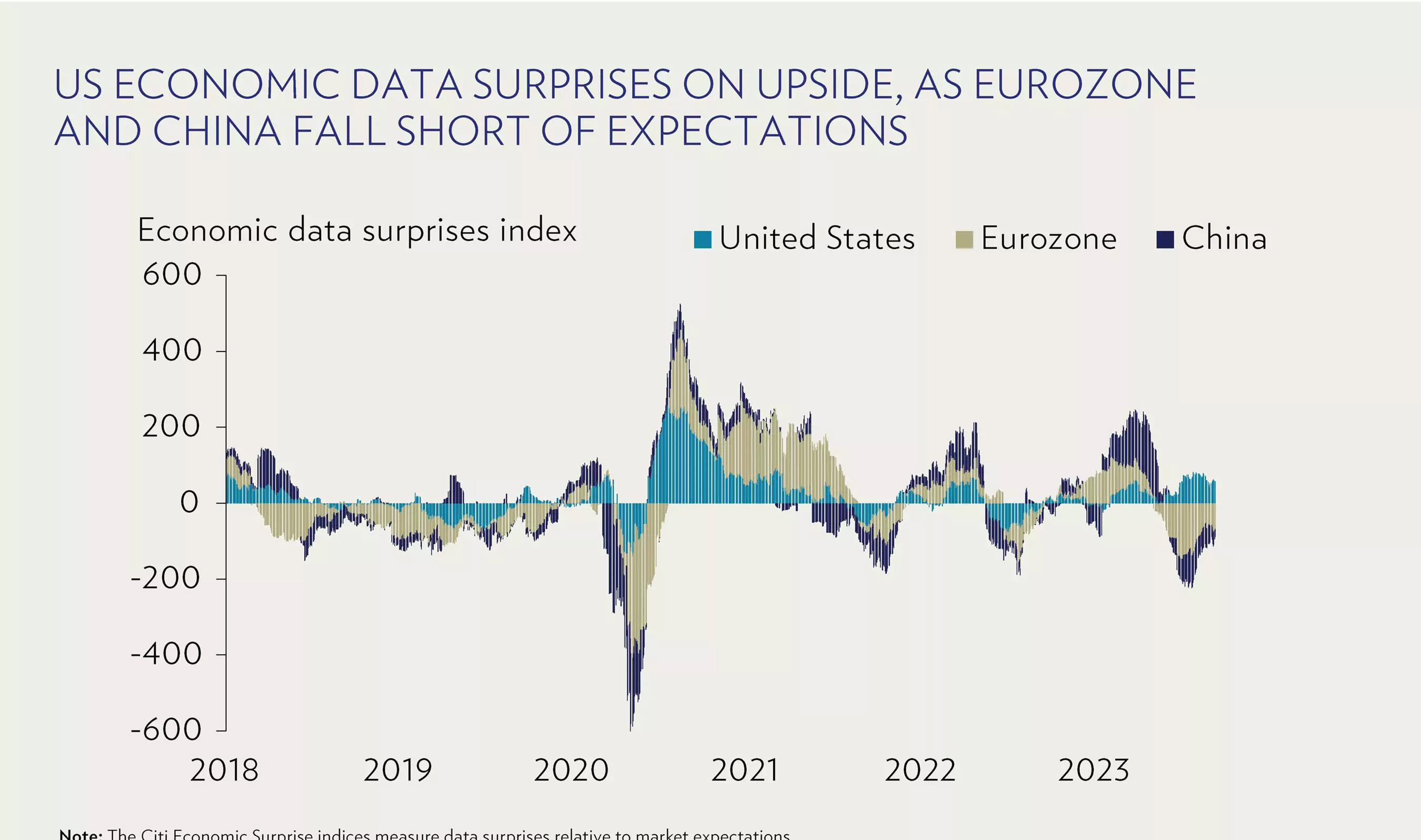

The three major economic regions, the US, the eurozone, and China, are at three completely different points in the economic cycle. In the US, the disinflation progress is intact, while economic activity is holding up better than expected. In the eurozone, inflation is proving to be stickier, while economic activity is slowing faster than in the US. In China, deflationary rather than inflationary trends are a cause for concern, and economic activity has also recently fallen short of expectations.

Withstanding interest rate shocks

In the US, investors are still perplexed at how well the economy has been able to withstand the interest- rate shock over the last 18 months. Some have even started to wonder whether monetary policy has become ineffective. Indeed, the monetary policy transmission mechanism is different in this cycle.

Households and businesses came out of the Covid-19 pandemic with strong balance sheets. Moreover, net private sector interest expenditures are not following the policy rate trajectory at this juncture, as financing was locked in at historically low rates before the US Federal Reserve embarked on its tightening path. In addition, generous fiscal transfers enabled both households and companies to increase their cash holdings, which are now also generating a decent yield again.

The case is different for US small caps, as they tend to have more floating and short-term debt compared to their large-cap peers. As a result, while higher interest rates have had a positive impact on S&P 500 earnings on a net basis, i.e. when interest payments on debt instruments are netted against the interest income on cash and cash-like instruments, they are beginning to weigh on the profitability of both publicly traded and privately held smaller US companies.

US fiscal policy driving the tide

Beyond the ramifications of an unambiguously restrictive US monetary policy stance, it is mainly US fiscal policy that is driving the tide these days. Chief Strategist at Clocktower Group Marko Papic argues that the Washington Consensus prescription for managing economies primarily through monetary policy has been abandoned and we are now in a Buenos Aires Consensus regime in which fiscal policy dominates.

Admittedly, it is much more difficult for investors to read business cycles when such a paradigm prevails, not least because in fiscal policy there are sometimes considerable discrepancies between announcements and actual implementation. However, in the realm of monetary policy, calculating and monitoring monetary aggregates and private sector credit trends, is relatively more straightforward.

Overall, the US is running a fiscal deficit that has widened over the course of this year. This extensive use of fiscal policy increases macroeconomic uncertainty. Estimates for the neutral level of interest rates in the US economy have recently been revised upwards, probably because bond investors require a higher risk premium to compensate for much higher uncertainty regarding the long-term inflation average.

Ten-year break-even inflation expectations have behaved well, currently standing at 2.3%, but the dispersion around this mean is likely to be much higher than in the last decade given the presence of both disinflationary and inflationary structural forces.

The forces pulling inflation down

Indeed, the forces pulling inflation down structurally are technology, debt, and ageing demographics. Technological progress contributes to disinflation by enabling productivity gains and the provision of goods and services at lower prices to consumers. Debt, which is higher around the world more now than ever before, as a result of rapid financialisation, has weighed on consumption in Western economies over the past decade. This is because private-sector agents have chosen to repair their balance sheets.

Such behaviour was once again observed in the aftermath of the pandemic outbreak. Demographic ageing tends to slow consumption growth and contribute to disinflation because older people are likely to spend less than their younger counterparts. However, evidence on the impact of demographic ageing on inflation is mixed. This is because if it is caused by a decline in the birth rate, which reduces labour supply and leads to higher and more sustainable wage increases, it can also prove inflationary.

Another force that structurally fuels inflation is the energy transition. The global economy’s shift to net-zero emissions will require massive investments in the short term, thus increasing price pressures in the economy.

The impact for investors

What are the implications of the current situation for multi-asset allocators? Right now, we think bonds would represent a great opportunity if inflation were to return to an average of 2%. For the first time in 16 years, the free-cash-flow (FCF) yield on US large-cap equities just turned marginally lower than the yield on 10-year US Treasury bonds. However, we expect long-term US inflation to average above 3%, which still makes a compelling case for equities strategically.