Don't worry about the noise on the m

The prospect of a technical default of the US government kept investors on their toes for weeks. Now that it’s off the map, investors are wondering: ‘What should we worry about next?’ In this Research Weekly, we consider what the aftermath of the debt deal and recent US employment data might mean for rates.

Financial markets, it seems, are always looking for something to feel anxious about. Having spent weeks fretting about the lack of an agreement on the US debt ceiling, those fears have flipped completely. Now the markets are worried that last week’s agreement will lead to the US flooding the world with new debt.

As usual, the doomsayers operate with ‘shock and awe’. Some claim the US will issue six times their annual Treasury bill volumes within six weeks. Even if it turns out to be smaller, the amount of liquidity this will absorb will be felt in fixed income markets – if not beyond. First of all, rates at the shorter end of the curve will likely be under upward pressure. This, in turn, could trigger some ‘wobbliness’ elsewhere.

Against this backdrop, we advise investors to be patient and ignore any liquidity-driven swings in the days and weeks ahead. The notion of economic growth becoming scarcer in the foreseeable future speaks in favour of investing in quality and growth stocks – or a combination of both.

What does the debt deal mean for rates?

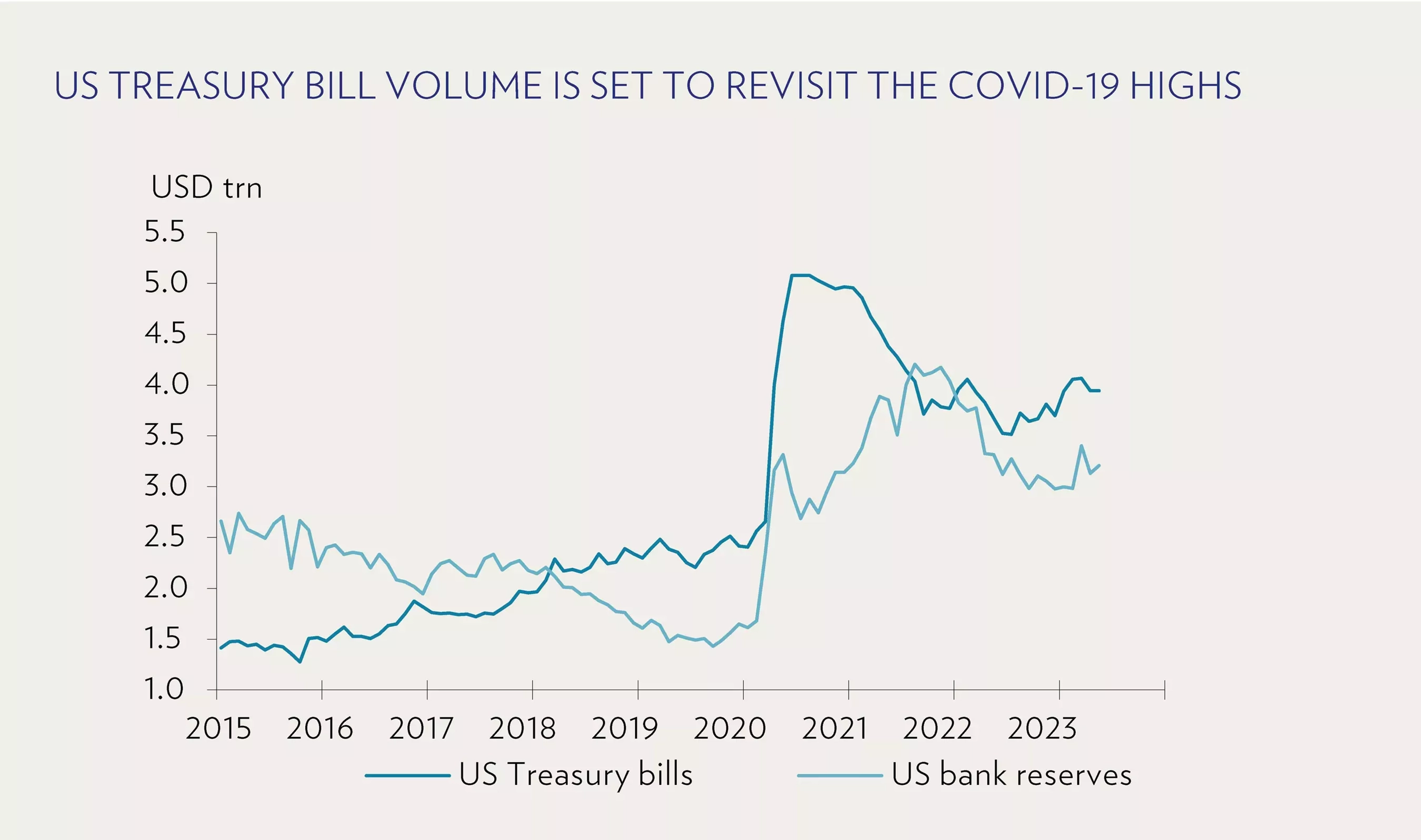

Over the last five months, the US Treasury has not been able to raise new debt, but it needs to cover a lot of pent-up refinancing in a very short period of time. Up to USD 1 trillion or more of Treasury bills will come to the market in the next couple of weeks. We reckon the Treasury needs to offer more than the 5.15% that the Fed pays on reserves or the 5.05% it offers on overnight reverse repos to place all these bills. This will keep money market rates firm for the time being.

The more the US Treasury issues bills and replenishes its deposits with the Fed, the more money will leave the banking sector. Concerns are thus rising that the combination of a quantitative tightening by the Fed (balance sheet reduction) and a Treasury refinancing is siphoning too much liquidity too fast from the banking system.

In such an environment, banks will have to fight harder for funding or ultimately cut their lending books. The implied credit tightening and slowing of inflation alike argue for rate cuts in the not-too-distant future. We look beyond the noise in the shorter term and maintain our call for longer duration.

‘Mixed bag’ labour market data complicates Fed’s decision-making

Close to a debt issuance bonanza, policy mistakes rank high up on the ‘wall of worry’. The Fed has told us they are ‘data dependent’, but what does that mean if the data coming in is as inconclusive as the data in the latest US employment report?

Friday’s employment report for May brought yet another upside surprise in job growth, with non-farm payrolls surging by 339,000 versus consensus expectations of 195,000. Furthermore, data from the past two months was revised up by 93,000, adding to the picture of red-hot job growth.

However, the strength of job creation might be slightly overstated in the payroll survey. In fact, data from the household survey in the report showed a decline in employment and a rise in the unemployment rate, to 3.7%.

The confusion caused by the mixed data – with the surveys drifting apart – does not make it easier for the data-dependent US Fed after the resolution of the debt ceiling and the recent rise of the core personal consumption expenditure deflator had revived expectations of a rate hike at the 14 June meeting. However, at a roughly 25% implied probability, expectations of a June hike have receded as compared to the beginning of last week.

Fed likely to play the waiting game

Nevertheless, due to the recently better economic data, markets appear to expect a ‘skip and hike in July’ scenario, with the probability of a July hike higher, at roughly 80%. The Fed has recently sounded more cautious regarding the need to hike rates further and called off any action in June before heading into the 10-day blackout period that began on 3 June.

We stick to our view that, despite recently better economic data and upside risks to our projections, the Fed is more aware of the delayed impact of the vast policy tightening provided so far and will rather hold from here on until rate cuts come into focus later this year, when policy tightening causes growth to cool.